hurdling with jason chatfield: new yorker cartoonist + comedian

on how to make sure your work is uniquely yours, getting blocked by donald trump (yes, that one) and what it's like having larry david hate your work

I’m beyond buzzing to bring you this interview with a man whose work prompts an unhealthy amount of shares to my Instagram stories. That man is Jason Chatfield, and he is an Australian cartoonist and comedian based in New York. Jason is Australia’s most widely-syndicated cartoonist, producing the iconic 102 year-old comic strip Ginger Meggs which is published daily in over 30 countries. He is the portrait illustrator for Waking Up, the award-winning meditation app created by the American philosopher and neuroscientist Sam Harris.

Jason’s cartoons have appeared in The New Yorker, The Weekly Humorist, American Bystander, Wired, Esquire, Airmail, Variety, MAD Magazine and many more. You’ll have likely seen many of them pop up on your Instagram feed, via the New Yorker Cartoons account (which is also where you’ll see me share them from too, probs).

His art has been exhibited in France, the UK, Australia and all over the United States, and his illustration work has been published through Simon & Schuster, Harper Collins, Penguin Random House, Humorist Books, Scribe Media and Libra Press. Until recently, Jason was the President of the National Cartoonists’ Society, and was previously President of the Australian Cartoonists Association. He is the youngest cartoonist to ever hold either of these positions.

Jason has worked as a stand-up comedian for 16 years and also appears on the Food Network as a Judge and Host on the TV Series, Buddy Vs. Christmas with Buddy ‘Cake Boss’ Valastro.

Here, Jason tells me all about his life as a cartoonist, why being a notorious eavesdropper is essential to art and how existentialism is actually pretty funny when you look at it with the right set of lenses. Oh, and why you should never work for free in the name of ‘exposure’, what it’s like to be blocked by the 45th President of the United States of America and how he felt when Larry David hated Jason’s caricature of him.

This was such a joyous, insightful and generous interview with Jason and I hope you love it as much as I do.

Q: When you were younger, what did you want to be when you ‘grew up’?

I’m pretty lucky because I always knew what I wanted to be. Despite a brief time at the age of seven when I thought I wanted to be a train driver, I always aspired to be a cartoonist. It’s all I’ve ever done – seems crazy that I got to do it as a job, considering it’s such an endangered career these days.

Q: Tell us about your first job. Where did you work, how did you get that job and what did you learn?

The first job I got as a cartoonist was at a local newspaper, The Fremantle Herald. I got a phone call (remember those?) from a fellow Perth cartoonist who told me there was a job going at the Herald, and I should send them some samples. I emailed the editor as soon as I got off the phone, and within an hour I was in the car on my way to meet in person.

I drove an hour to get to the office, which was one of those old dusty wood-floored newsrooms with sticky notes and proof sheets stuck up on a sea of makeshift cubicles. The heady scent of newsprint and day-old pizza wafted throughout the office. It was intoxicating. The editor, Brian Mitchell, sat me down and told me some hard truths about my work, then offered me a job on the spot– $50 per cartoon, and if I wanted to do some proof-reading, ad layouts, or copywriting work I could do that, too, for $10 bucks an hour. I would pull 20-hour shifts for the following 3 years learning everything I could about the newspaper business, eventually doing 6 cartoons a week on wildly varying topics. I still freelanced for them doing spot cartoons for 15 years after that, but sadly newspapers have had their day. The skills I learned at that job held me in good stead to this day.

Q: Tell us about your worst ever job. Why did you hate it? What made it so bad?

My worst-ever job was working as a costumed mascot for a pizza shop in suburban Perth. The pizza shop, called Pizza Haven, was on a highway, and it was my job to stand for hours in the middle part of the highway during peak hour holding a big foam-core sign that said $5 pizzas. The problem was, that the guy who quit the job before me had thrown up inside the head of the koala costume. They never cleaned it out. So I never wore the head of the costume– I’d take it out to the highway with me to satisfy my boss, but I’d never put it on. So I guess the passers-by were really confused as to what I was meant to be. A sasquatch with a pizza sign? A hirsute young boy looking for the rest of his kind?

Dogs would bark at me. Sometimes people would throw things out of their car windows, and I’d have to use the sign as a shield. They’d fling whatever was within arms’ reach: bottles of coke, bottles of pee, a bag of lemons. The day my older sister got her driver's license she made it her first priority to drive past and hurl a sandwich at me going 70 miles an hour. I didn’t see it coming so the back of my head was covered in mayonnaise for my whole shift.

23 years later, I used the experience in my comic strip.

Q: In 2017, your first cartoon was published in the New Yorker Magazine. How did it feel? What was your path to this point? How long (and how many submissions) did it take to get your first publication? What advice would you give to illustrators and artists trying to do the same thing?

That’s right – 2017 was a big year for me. On the last day the Cartoon Editor, Bob Mankoff, was taking meetings before being turfed out the door, he finally bought one of my cartoons. I’d been submitting for years, but never in person until I moved to New York in 2014. I would go in and meet with him, he’d give me advice, reject every cartoon I pitched, then I’d go back to my studio, weep into a bottle of something, and start over.

You submit 10 cartoons in each batch and wait for an email at 5pm on Friday. If the email doesn’t arrive, you didn’t sell. It’s a sadistic ritual, really. Needless to say, it was a big day when I finally sold my first cartoon. There was something legitimizing about being published in print in the New Yorker, even though I’d been published hundreds of times before in newspapers. This felt different. I’ve since been lucky enough to sell many cartoons to them, but that first time will always be the most exhilarating.

The advice I would give any artists or illustrators trying the same thing is: First of all, don’t look at what anyone else is doing. Make your work as unique to you as possible. Don’t copy anyone else’s style, tone, or jokes – just try to stand out by being as singular as you can. It’s a hard lesson to learn because the temptation is to see what’s getting published and curate your work to that. If some style is trending on Instagram, it’s a good sign of something to avoid doing, because it’ll just as quickly go out of style. Then you’ll be left with something nobody wants to use (plus, everybody else already did it, and probably better).

I can’t stress enough just how debilitating it was to figure out some kind of formula for success in cartooning, and then realize the formula, paradoxically, is to not follow any formula.

Q: Your cartoons, especially those found in the New Yorker, are incredibly spot on at capturing the zeitgeist and the mood of the reader. Where do you find your inspiration and ideas? Are you a notorious eavesdropper for insight?

I’m a notorious eavesdropper, yes. I think the best cartoon ideas I’ve ever had were sparked by overhearing a snippet of conversation out of context while walking past someone on the sidewalk. The key is to stop walking around with your AirPods in. New York really does give you all the material you need if you’re willing to listen out for it.

I think the other piece to it is absorbing the way people move, and the way they dress. The way they hold themselves when they’re with friends vs. when they’re alone – also their hair. Hair says a lot about a person without them having to speak a word. I think hand gestures are also much better at conveying an emotion than any facial expression. Sometimes the hands are saying something the face isn’t, and the discord between those things is its own joke.

I also read a lot – mainly fiction, but sometimes non-fiction about human nature: Daniel Kahneman, Sam Harris, or Yuval Noah Harari get a lot of re-reads. Oliver Burkeman is another favorite for non-fiction. They spark a lot of inspiration for the ‘bigger’ themes in my work – existentialism is absurdly funny when you look at it with the right set of lenses.

Q: There’s a lot of ‘free work’ in the name of ‘exposure’ that happens in the creative worlds. How do you strike the balance between discerning what is genuinely a good opportunity to do something for free because it genuinely will open doors, versus being exploited for your talents instead?

Yeah, I definitely get it, but I strongly discourage it. Sometimes it’s tempting to accept a high-profile gig for free because it seems like it’ll be good exposure. The person asking promises you’ll get credit on their Instagram, or they’ll share it with their followers. The thing is, once those people see it, they’ll be in your DMs asking you to do something for THEM for free, too. It’s an endless spiral. (Learning to say NO is a really difficult skill for freelance artists to learn, but it’s essential.)

If you’re doing a gig for free to get in front of the right people, you should at least have the courage to ask for something. If that’s a tip, or a voucher. Just giving work away for free hurts the artist and the art itself – it also screws every other artist struggling to justify charging for their work. If one person is giving it away for free, why would anyone want to pay someone else? As if it isn’t already hard enough with A.I. generated art taking the small jobs that artists rely on to bridge the gap between rent days, we shouldn’t have to be worrying about fellow artists giving away their work for ‘exposure.’

Q: As an Aussie living in Manhattan for 9 years, you’ve said you still don’t describe yourself as a ‘New Yorker’. What do you think it would take for you to describe yourself as one?

I think I’m pretty close to calling myself one. In May of this year, it’ll be 10 years since I moved to New York, which some people think is the official demarcation between ‘person who has lived here for a time’ and ‘person who lives here’. I’ve been doing a bit on stage (I do stand-up comedy at night) where I say everyone has a different answer to this question – “You’re Not A Real New Yorker Until…” and audience members shout out the most random answers. One night a girl said “I heard, uh, You’re not a ‘real’ New Yorker until you see an NYU student get hit by a cab? Is that… one?” That’s… just a crime. But I know some people have very specific requirements for what constitutes a “real” New Yorker. (Incidentally, I have a book of over 100 cartoons coming out in Winter 2025 called “You’re Not A Real New Yorker Until…”)

Q: You were blocked by Donald J Trump on Twitter during his presidency after you replied to one of his tweets asking him if he was drunk. How did it feel?

That was a real badge of pride for a comedian. It was early, too – 2016! It meant I never had to see any of his inane tweets for the entirety of his Presidency. Bliss. I had made fun of one of his stupid tweets that he’d fired off from the toilet at 3am one morning, and it got a lot of likes and retweets. I guess because I had a ‘verified’ tick next to my name he felt it was a good use of his time to find me and block my account. It definitely feels weird to be blocked by the leader of the free world while you’re between subway stops on your way home.

Q: Cartoons and portraits are often highly personal. You’ve spoken about your experience as the portrait illustrator for Sam Harris’s award-winning meditation app, Waking Up, and about how much you enjoyed making ‘each portrait fit the tone of the person, and the topic they were talking about.’ How do you go about making sure that each portrait does exactly that? Why is it so important?

I spent more time than I probably should trying to get the portrait to look like the person sounds… if that makes any sense. My favourite caricaturists, like Mort Drucker or Al Hirschfeld always captured the entire ‘spirit’ of their subjects, not just the likeness of their facial features (though they always nailed those, too.) I think if you’re going to do the work of capturing someone’s likeness, you owe it to them to at least find out a bit about them and see if the tone of the art fits their personality. I listen to every conversation guest Sam Harris has on the Waking Up app. Sometimes I’m already familiar with their work, but other times I have to try and figure out whether I’m ‘sticking the landing’ on these. I have to say, I don’t know if I get it right every time, but my hit rate is, thankfully, pretty solid.

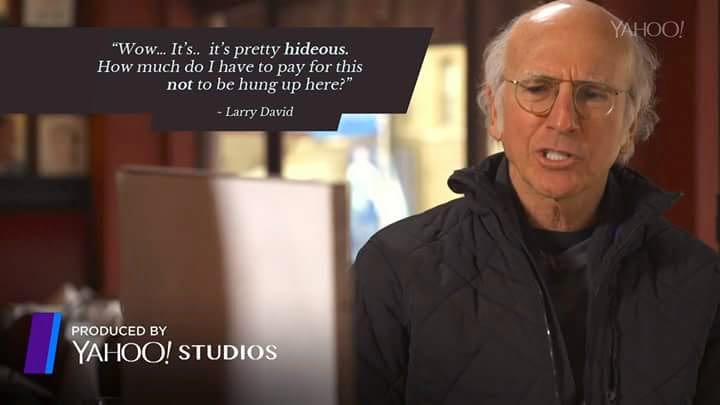

Q: Speaking of portraits being highly personal, Larry David hated the one you did of him for Sardi’s restaurant (a famous restaurant in New York known for the caricatures of Broadway celebrities on its walls). Larry said, ‘Wow… It’s… it’s pretty hideous. How much do I have to pay for this not to be hung up here?’ You said that you loved that he hated it. Why did this bring you so much joy?

I think the reason I loved this so much is that Larry is one of my heroes, and if he said he loved it I’d have known it was a blatant lie. It’s also way funnier (and on brand) if Larry hates something than if he’s kind and appreciative. Larry the person (not the character) is a very nice guy, and I know he’s kind. But what kind of story is that? “Larry saw my caricature and loved it!” Boo.”

In truth, we both hated it. I was instructed by the agent who commissioned it (through Katie Couric) to make it ‘not’ look good because all of the caricatures on the wall at Sardi’s look nothing like the people they purport to depict. In that tradition, I had to ‘dumb down’ my style to make sure it looked ‘just enough like Larry’ to be a caricature, but ‘terrible enough to be hung at Sardi’s.’ It was much harder than I thought to do a ‘bad’ caricature because you have to deliberately forget everything you’ve learned about drawing.

He signed a copy for me, but I refuse to hang it in my studio because it looks so terrible.

Q: You’re a stand-up comedian too. Aside from the fact that I’m assuming most of your cartoons are drawn sitting down, how do the differences in these jobs compare? What do you get out of the differences?

The only difference is the lag time between telling a joke and hearing the reaction. With cartoons, it takes days, sometimes weeks. With comedy, it takes seconds. I’m lazy, so I prefer the second method.

Q: You’re also the President of the National Cartoonists’ Society, which brings together over 500 of the world’s major cartoonists and gives them an opportunity to get together and enjoy each other’s company – as well as ‘stimulating and encouraging interest in and acceptance of the art of cartooning by aspiring cartoonists, students and the general public. Can you tell me a bit more about this? Why is this society so important for cartoonists? How do you get in?

I have just finished my time as President of the National Cartoonists’ Society after four (very challenging) years. I think organizations like this are important to hold together the thread of history of our industry – whether that be through awards, stories or otherwise. I don’t know of any other thing that has survived in cartooning as long as the NCS. Magazines, comics, books and newspapers have come and gone at various life-cycles, but the collegiate relationships and deep friendships that the NCS has fostered have remained. I think I’ve learned more from my fellow cartoonists than any course or school could have ever taught me. Which is lucky, because I never went to art school. To get in, you have to be a professional working cartoonist.

Q: What’s the biggest hurdle you’ve ever had to get over?

My own mind. It’s my biggest critic and my worst saboteur. I feel like I’ve spent more time in my career trying to figure out ways of working around my brain than just sitting quietly and drawing. It’s a bit of a mess. Meditation helps. Also drugs. (I’m kidding. I never meditate.)

Q: What’s a recent hurdle (big or small!) you’ve had to get over?

I had to figure out how to actually charge what I’m worth recently, which is frustrating because I know I’m a professional. I’ve been doing this for 20 years and I still doubt whether I can justify what I’m charging. It’s just my inner critic doing its thing where it scoffs at the amount I’ve sent in an estimate, right before the client comes back with “Oh, great! Is that all?”

Q: What’s the biggest mistake you’ve ever made at work? What happened? What did you do? And what did you learn from it?

I think Derek knows what he did. And I think it’s best we never speak of it again.

Q: Is there anything you wish you’d done differently over your career? If so, what?

I wish I’d documented more of the process. I got so caught up jumping from deadline to deadline that I never wrote down the process of much of the work I did. I look back on some of it now and wonder “how the hell did I get that line?” or “Where is the file with that watercolour wash background?” – Everything was done so frenetically I can never go back and reverse engineer any of it.

Q: Anything to get off your chest?

This leach. It's been there for days, and I still have consumption.

Anyone want this?

QUICKFIRE ROUND

Q: One work-related object you can’t live without?

My moleskin. It follows me everywhere. (Even to bed. And the shower.)

Q: Best advice you’ve ever been given?

Enjoy the process.

Q: Worst advice you’ve ever been given?

Do it for the money.

Q: Your favourite subject to draw?

Dogs.

Q: The person you admire the most?

My wife. For putting up with me.

Q: Ever faked being sick to get off work?

That would assume I have a boss to report to… (But yes, I’ve definitely emailed myself to tell myself I’m not feeling well because I ate a bad prawn, and took the day off to visit The Met.)

Q: Any last words?

Wait, where did that gun come from and why is it pointed at my he–

Jason’s new Substack, Process Junkie, launches this month, and it’s all about the creative process of making art. You can sign up for free here.